A single lamp, called a ghost light, would burn all night in theatres like the ones where RH Thomson acted and directed. They would banish darkness after a performance for safety reasons, but RH said that often after the directors and actors had gone home, he would linger in the dim cavern by the ghost light and try to hear the echoes of the characters’ lives that were played out onstage.

RH has written a book about wars and families called appropriately “By The Ghost Light.” He traces his family’s involvement in the First and Second World Wars, and uses that history as a lens to discern the meaning of war. He invites us all to share:

He had eight great-uncles who fought in that war. Of the five on his father’s side, two died in battle and two more died in the following years as a result of lung damage from poison gas. None of the three on his mother’s side made it to Armistice.

There are three narratives that shape our perception of war, RH writes. There are the war-mongers’ stories before fighting breaks out, the chaotic battlefield dispatches and the mythologizing that follows. It is a toxic formula that perpetuates war.

Far from being an abstract historical exercise, RH writes a narrative with a heartbeat. With 50 years perspective as an actor and director, he has started a project called The World Remembers, to assemble the world’s first global memorial to everyone killed in the First World War. It is radical because it transcends nationality, on the thought that in death equality should rule. As one soldier told him: “When we soldiers are beneath the ground, we are equal.” Each body would be named, each would be given a headstone, and officers and commoners would lie side-by-side.

It could easily, over time, be extended to WW2, Korea, Vietnam and onwards.

In contrast to the equality of the dead, the common factor among war’s casualties, he notes, are the civilizations that fight them. WW1 saw the disappearance of the courtly life of the Emperors and aristocracy whose house-of-cards fragility caused the war. WW2 brought democracy to the former empires of Japan, England and Germany. Vietnam and Iraq ended America’s global confidence in its global vision. And Ukraine is today shredding the Russian enterprise of one-man rule.

A dark positive of Vietnam is that the names of every dead American soldier is inscribed on a memorial; the negative is that the Vietnamese names are absent.

Military imaginations after WW2 pushed back on the idea that war was a ‘gallant’ enterprise. But war-as-glory is creeping back among the Russians today, because their president is re-establishing his country’s former imperial reach. As you watch Putin proceeding through his public appearances through the former Tsar’s Moscow residence you can see very real nutcracker soldiers open the golden doors before him, and their heads pivot as he passes, drilled to keep their heads high and chins angled.

This contrasts with the almost shame-faced behaviour of German troops today, who say “we do not do parades.” Or with the Canadians, who have become a country of all peoples, with no hunger for military glory.

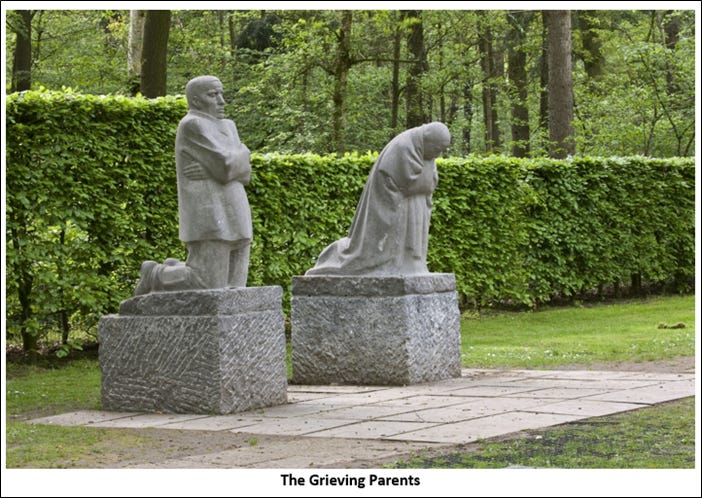

The universality of the pain of war is perhaps symbolized best, according to RH, by a sculpture created by Käthe Kollwitz, the mother of a son who was killed in 1914, in the opening month of the First World War. Called the “Grieving Parents”, the stone figures depict a father with his arms wrapped around his chest, bearing down on the sorrow that threatens him from within. The woman is bowed by pain. The statue is replicated in many graveyards, for the dead of many wars. Kollwitz’ grandson was killed in 1941 fighting in Russia. She herself died in the Spring of 1945, just before Germany’s surrender. She said that war had followed her for her entire life.

The ambition to raise the recognition of the humanity of the common soldiers faced some inbuilt indifference. Britain has a long history of regarding its common (lower-class) soldiers as expendable. After Wellington defeated Napoleon at Waterloo, British merchants collected any bones that remained on the battlefield, carted them off to England and ground them up to be sold as fertilizer.

Armies only began to record the names of their dead because they needed to know how many troops were available to fight the next day.

We are all subject to time’s winds that will inevitably carry us away. We do our best to set sail for the voyage of our lives. Our devices are religions, clocks, histories, philosophies, prayers, family stories and seed vaults. But so far, no one has been able to sail forever.

RH flags an interesting balance in timing. Ancient artists who worked in the Chauvert Cave drew their sketches 35,000 years ago. Their paintings of cave bears, horses and other animals were accompanied by personal hand-prints; one of the painters had a crooked little finger.

The murals said: “Here I am; this is what I made; this is what I saw.”

Today a NASA probe, Voyager 2, is carrying a gold-plated disk towards Andromeda. It has recordings of our music, art and speech. It will arrive in an areas where there might be Earth-like planets, in about 36,000 years.

The disk says: Here I am; this is what I made; this is what I saw.”

We are in the halfway point between those declarations from past and future. “By these marks, know that we existed”.

Much of our most important work continues to be the recording of the testimony of our existence. This is not a job for artists, but for everyone.

RH describes a 12-year-old girl whose job, along with 300 other women, was to sort the shoes of the 18,000 Jewish men, women and children who were being executed at a concentration camp in Poland. The girl lived and worked on a desolate road until she herself was murdered some months later. Yet she found extraordinary words to write poem that has survived. It was her version of the cave art or the NASA probe. She wrote in part that:

The rain pours over them without a sound, like tears

They are burnt by the sun.

They are sorted by nervous, trembling hands,

The piles grow, piles like giants,

Becoming pyramids,

Rising above themselves,

Thrust into the sky like columns

Shouting: Why, why, why?

Here I am. This is what I saw.

As Carl Sagan summed up: We are a way for the cosmos to know itself.

So why should we remember the German war dead?

Because as Keynes said, the difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas, as in escaping from the old ones.

Cruelty needs to be remembered. Back in the days of colonial empire, Belgium’s king caused as many deaths in his colony of the Congo Free State as the population of Belgium itself — some seven million people. The Congo was owned by a private charity run by Leopold II. Yet to make profits from the rubber trees, his soldiers destroyed a nation.

In Belgium itself, many Canadian soldiers were buried alive in the artillery bombardment of the First War. Among them was one of RH’s uncles. His body had been lost in one of the many visitations of artillery shells in the cemeteries. Exhumation teams looking for lost bodies would used long steel rods to probe the earth. Should they hit something, they would remove the rod and smell the end for purification. If there was a body they would dig for it. RH’s uncle was never found, so he remains an “unknown”. Yet the words of the dying apply:

And in his eyes

The cold starts lighting, very old and bleak,

In different skies.

The author who wrote that, Wilfred Owen, felt that only of he excelled as a warrior, would he be widely accepted as a war poet. He succeeded in getting a medal for gallantry. But he had been killed by the time the announcement was made.

The kind of sentiment that he expressed is actually a liability for a military system. He was saying: “be careful if they call you a hero, because that means they don’t care if you die.”

To mobilize anger like his, would more suit the actions of a robust democracy than a dictatorship. A democracy needs an electorate that believes in collective action.

This belief is eroded by the rising tide of economic inequality. If you think a CEO deserves higher compensation because their job has greater responsibilities, then you haven’t escaped the mindset in which the working-class ‘soldiers’ are not only subordinate to business executives but also that their lives are worth less. If you believe that the life of a CEO and the life of a soldier are of equal value, then you must explain why a soldier is so poorly paid.

The assumption that executives must make millions because large pay packages are needed to attract the talent needed to run large corporations is a conclusion arrived at while standing in a hall of mirrors. It reflects the values only of the men and women who endorse it. The conclusion is credible only if you live in a world of assumptions about executive pay.

The same warp transfers to the military when private companies get involved. Blackwater’s private soldiers got paid twice the amount of US army soldiers, yet did not do any combat work. By 2010, their 260,000 men outnumbered the deployed US military forces in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The nation has assumed the role of feudal baron: peasants work, the aristocracy run mercenaries for profit.

To date, more than 20 Great War nations have agreed to participate in the RH remembrance project, and 4.5-million names have been assembled — all of which will be displayed. “So, the act of naming the nine and a half million — we’ve only got four million so far — is to reach out to everyone and say, ‘Let’s make an inclusive history, an inclusive remembrance.’ And, in the seeds of that, you start to de-escalate conflict.”

Thomson also argues wars aren’t just about soldiers, but the families they leave behind. He spends three chapters of the book talking about the women back home — the nurses, the mothers, the sisters.

The World Remembers commemoration is RH’s response to a thousand years of neglect of the soldiers who died in battle. It is his vengeance on the fertilizer merchants of England, and to Remembrance Days when we remembered only our own dead.

By The Ghost Light, then, is about more than a light on a stage illuminating a dark theatre. It is about a way to see the light of the millions of ghosts of world wars — not just to see them, in fact, but to see their stories as narratives of a common tale.

“Here I am; this is what I made; this is what I saw.”

He concludes: “The echoes of our voices never really leave the building. I have stood on empty stages and felt the presence of those who performed there before me — which is why theatres always seem somehow inhabited and why the ghost light is left on.

“We have only to find someone to pace the stage again, remember, and listen.”

Written by Barry Gander

A Canadian from Connecticut: 2 strikes against me! I'm a top writer, looking for the Meaning under the headlines. Follow me on Mastodon @Barry

There will always be wars & leaders who lie to us about all its aspects. Repercussions of one engender the next. Trying to learn history on one’s own is frustrating as you either have to start from caveman time to see how each skirmish engendered the next, or you go to Wikipedia and have them refer you to a previous war for the causes of the one you’re researching, like nesting dolls.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

Yes, the idea of war-as-glory should have died during the "Great War" as the technologies of warfare sapped all the "glory" out of armed conflict. The inhumane trench warfare of WWI is being recreated in the frozen muddy fields of Ukraine and sadly we in the West complain we are bored with the lack of spectacular "glory" in this barbaric slugfest.

What is frightening to me is the rise of glorious new technologies that promise clean "surgical strikes" rather than the indiscriminate civilian slaughter and destruction seen today in Gaza. Not only is there no longer any "glory" in war but no real end point either. Endless wars such as Iraq and Afghanistan rage and smolder with embers of hatred waiting for fuel to ignite them again.

General Robert E. Lee said: "It is well that war is so terrible, otherwise we should grow too fond of it." How terrible must it become before we lose our taste for such bitter hatred and suffering?