They called her “Bouctou” — the one with the big belly-button.

When they migrated north in September, the Arab caravans would leave their baggage in her care.

On their way back, they would tell friends of their destination: “We are going to Tin-bouctou,” they would say, the well of Bouctou.

When I was a kid, I hitch-hiked to Timbuktu. Back home, I had I worked in a fast-food restaurant to get the travel money. I had always wanted to go to Africa, and I was captured as a child by that old rhyme:

From Timbuktu to Kalamazoo,

To Kalamazoo and beyond.

Ironically, I’ve never been to Kalamazoo, even though it’s relatively close by in Michigan.

But Timbuktu is on the southern edge of the Sahara desert, sitting on a curve of the 1,000-mile-long Niger River. At that time, lush mango trees lined its banks, but I understand that the sands have encroached on it since.

Another plague has encroached on it as well: the hand of jihadists has closed on the area known as the ‘Sahel” — the semi-desert area covering half-a-dozen countries stretching from the Sahara Desert in the north to the tropical jungles to the south. Violence, conflict, and crime have surged over the last decade, transcending national borders and posing significant challenges to countries both in and outside the region.

Those countries comprise what I call the “Violence Vortex” — the area that has more terrorism deaths than any other region of the world. The Global Terrorism Index says it accounts for 43% of the world’s terrorism deaths.

I follow news about it because it is a barometer — if terrorism in the Sahel is going down, then the world is becoming a safer, better place. It’s not very scientific but it seems to work out.

Sahel countries for example are consistently ranked high on the Fragile State Index, particularly Chad, Mali, and Nigeria. Frequent transfers of power are a problem, with a combined twenty-five successful coups d’état between 1960 and 2022, most often resulting in the military overthrow of democratically elected civilian governments.

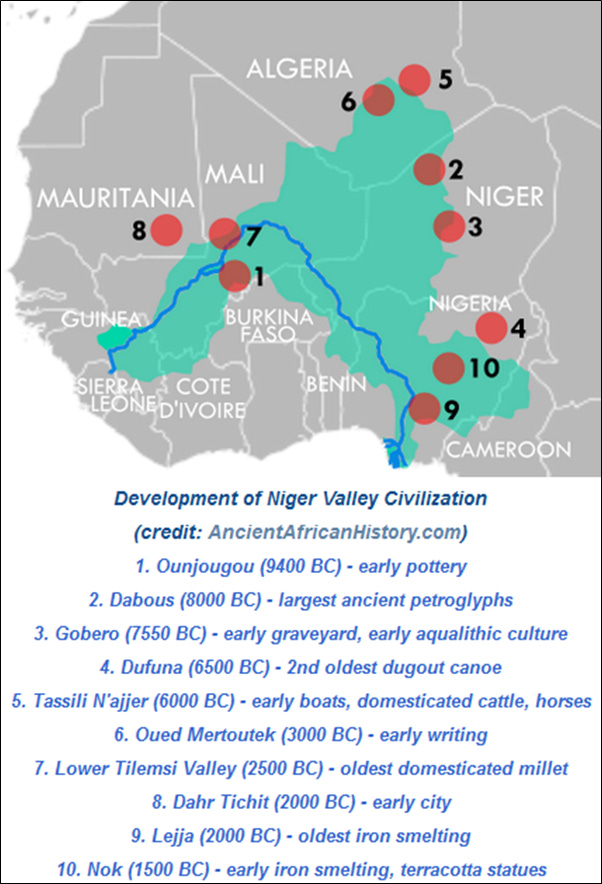

It is a perverse part of the world. The Niger River itself is the third largest river in Africa. It starts only 240 km from the Atlantic Ocean…but then insists on going on a boomerang loop of 4,200 km before emptying into the Nigerian coast.

Back in The Day Of Sail, that whole coastline was a mosquito-infested death-trap for white people. As the old British Navy saying used to go, mindful of the thousands of sailors’ lives that were lost:

Beware, beware the Bight of the Benin,

For few come out though many go in.

That darned coast almost killed me too, but for a different reason and it’s a different story.

When the sailors made landfall on the West African coast, they were the guests of the powerful African empires that have contested that land for centuries. The West African countries were the richest in the world, 2,000 years ago. They were far too strong to let the white slavers go ashore…the slaves were brought to the boats by African traders.

Writers as diverse as DH Lawrence, Agatha Christie and Roger Hargreaves used Timbuktu as references for the mysterious, the unattainable. In 1930, Lawrence wrote:

And the world it didn’t give a hoot

If his blood was British or Timbuctoot.

If anything, Timbuktu was even more exotic than they imagined.

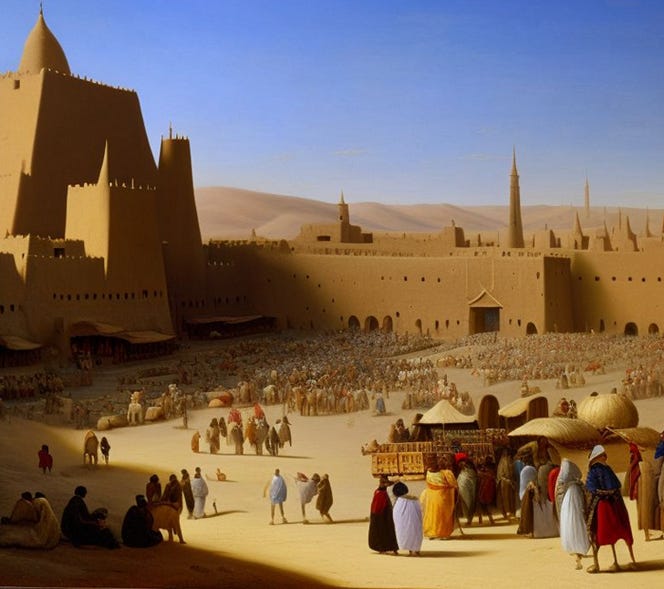

At the end of a five- mile-long canal that led from the western edge of Timbuktu to the Niger. it was a place where the sale of manuscripts was far more profitable than that of other goods…and Timbuktu was a centre of the gold trade.

Manuscripts in those times were loose, unnumbered folios enclosed inside leather binders, tied shut with ribbons or strings. They were brought from all across the Arab world; from places like the country called “sunset” (the translation of ‘Egypt’), Spain, Pakistan, East Asia…it was an empire of half the globe.

To the city came camel caravans laden with salt, dates, jewelry, Maghrebi spices, incense, European fabrics, and other goods from as far away as England. They arrived in Timbuktu after weeks crossing the Sahara. Boats sailed north on the Niger, bringing to Timbuktu, at the river’s northernmost bend, the products of jungle and savannah — slaves, gold, ivory, cotton, cola nut , baobab flour, honey, Guinean spices, cotton, and shea butter, an ivory-colored fat extracted from the nut of the African shea tree. Traders, middlemen, and monarchs made fortunes in the main currency — gold. When Mansa Musa, the ruler of the Malian Empire — a vast territory that subsumed parts of the collapsed Ghanaian Empire and also comprised modern-day Guinea and northern Mali — traveled in 1324 on the hajj to Mecca from Timbuktu, he brought several thousand silk-clad slaves and eighty camels carrying three hundred pounds of gold dust each. That would be $545-million today. And that was his Travel Fund.

In the late fourteenth century, Timbuktu began to emerge as a regional center of scholasticism and culture. And here emerged a side of Islam that few people consider today…a religion of knowledge, tolerance and exploration.

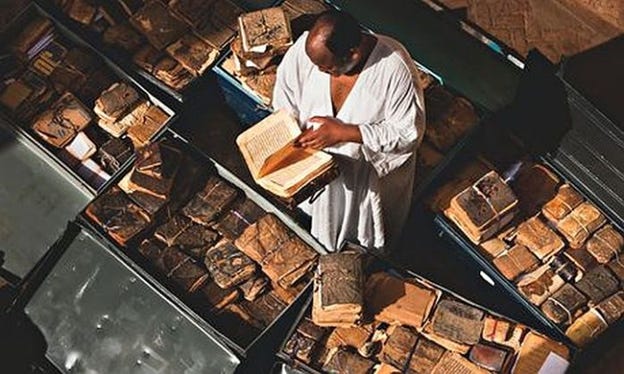

Scholars in Timbuktu copied books at the rate of one every two months — writing an average of 150 lines of calligraphy per day — receiving their compensation in gold nuggets or gold dust. These scribes employed proofreaders who pored over every Arabic character, receiving a percentage of the payment. A colophon — Greek for “ finishing touch ” — at the end of each work recorded the manuscript’s start and completion date, the place where the manuscript was written, and the names of the scribe, proofreader, and vocalizer, a third craftsman who inked the “ short vowel ” sounds that are not usually represented in Arabic script.

I do not pluck these details in from my own memory, but from a book called “The Bad-Assed Librarians of Timbuktu: And Their Race To Save The World’s Most Precious Manuscripts”. It was written by Joshua Hammer, who tells a worthy tale.

Despite occupations and invasions of all kinds since then, scholars managed to preserve and even restore hundreds of thousands of manuscripts dating from the 13th century.

When that was threatened by rigid jihadists determined to stamp out ‘heresy’, Timbuktu’s Librarian Abdel Kader Haidara organized and oversaw a secret plot to smuggle 350,000 medieval manuscripts out of Timbuktu. Joshua Hammer chronicled Haidara’s story in his book.

Most of Timbuktu’s residents, one traveler noted, didn’t observe the Ramadan fast, consumed alcohol, or limit their inquiries to Islam. Over time, the scribes widened their scope. They copied surveys of algebra, trigonometry, physics, chemistry, and astronomy. They translated into Arabic the works of the greatest Greek philosophers, Ptolemy, Aristotle, and Plato; the “ father of medicine,” Hippocrates; and the eleventh-century Persian philosopher and scholar Avicenna, who wrote dozens of manuscripts about ethics, logic, medicine, and pharmacology.

Their rulings were liberal for the day. One fatwa supported a woman’s decision not to sleep with her husband by arguing that men had often exercised the same right. Try that in Texas today!

Timbuktu’s astronomers studied the movement of the stars and their relationship to the seasons, accompanying their writings with elaborate charts of the heavens. They advanced arguments for the adoption of the earth-centered model of the solar system; Physicians issued instructions on nutrition and described the therapeutic properties of desert plants. They prescribed herbal remedies to help ease women through labor, toad meat to treat snakebites, and droppings from panthers mixed with butter to ease the pain of boil.

One of the most eye-opening volumes, Advising Men on Sexual Engagement with Their Women, served as a guide to aphrodisiacs and infertility remedies and provided counsel on winning back wives who had strayed from the marital bed. To help with his climax a man must drink the dried, pulverised testicles of a bull.

That began to change when Muhammad Abd Al Wahhab, an eighteenth-century preacher from the desert interior of what is now Saudi Arabia, urged a return to the austere Islamic society. I have been there too, and seen the landscape. I understand why these religions are so hard.

Al Wahhab declared holy war on Shi’ism, Sufism, and Greek philosophy. He formulated the doctrine known as takfir, by which he and his followers could designate as an infidel, and punish with death, any Muslim who refused to pledge allegiance to the caliph, fundamentalist Muslims who extol a return to the Islam practiced by the Prophet and his original followers, the Salaf, or ancestors — had constructed Wahhabi mosques both in Timbuktu and other desert communities, founded orphanages, and lavished cash on local charities.

That version of Islam is not apparent in the young men who had proudly displayed Osama bin Laden T-shirts after the attacks of September 11 .

They might have been graduates of a very different place than Timbuktu — Jeddah’s King Abdulaziz University, the fundamentalists ’ nerve center. It has been an incubator for some of the most virulent strains of Wahhabism. Osama bin Laden studied business administration there and received religious instruction from Mohammed Qatub, the brother of the Islamist revivalist Sayud Qatub, who established the ideological underpinnings of violent jihad against the West.

Abdullah Yusuf Azzam, the Palestinian Sunni theologian whose sermons on cassette had enthralled the aspiring young jihadi Mokhtar Belmokhtar, was a lecturer there before he recruited committed young Islamists to fight a holy war in Afghanistan against the Soviets in the 1980s, and founded Al Qaeda with bin Laden.

Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, which answered, like its counterpart in the Maghreb, to Osama bin Laden and Ayman Al Zawahiri, had captured Zinjibar, the capital of Yemen’s Abyan Province, and declared it the twenty-first century’s first caliphate. It was the initial step in Al Qaeda’s goal of sweeping away Muslim and Arab secular regimes and replacing them with a pan-Islamic fundamentalist state. Further emboldened by their victories in Mali, the radicals would pursue this goal with increasing aggressiveness. The triumph in Mali would inspire, at least in part, the seizure of much of Syria and Iraq by the Islamic State between 2013 and 2015.

As the militants were coming down from the north, the book-keepers of Timbuktu transported ninety — five percent of the 377,000 manuscripts from Timbuktu’s libraries to more than thirty safe houses around the city .

The jihadis of Timbuktu went on their rampage in July, destroying a dozen Sufi shrines. In August, Libyan Wahhabis, known as Najdis, outdid their Timbuktu counterparts. They desecrated dozens of graves in Sufi cemetery in Tripoli’s Old City..

The French army returned to Mali and ejected the jihadists. On the verge of being expelled from Timbuktu , the Al Qaeda fighters would exact their retribution. The men swept 4,202 manuscripts off lab tables and shelves, and carried them into the tiled courtyard. In an act of nihilistic vindictiveness that they had been threatening for months, the jihadis made a pyre of the ancient texts, including fourteenth — and fifteenth — century works of physics, chemistry , and mathematics, their fragile pages covered with algebraic formulas, charts of the heavens, and molecular diagrams.

And yet out of this wanton act of destruction the curators of the Ahmed Baba Institute had managed to extract a small victory. In a secret room in the basement there were dozens of metal shelves, as tidy and ordered as the stacks of a university library.

Inside were stacks containing 10,603 restored manuscripts, folios, and leather-encased volumes among the finest works in the collection. “All of them — untouched, ” Bouya Haidara said

Timbuktu had been the incubator for the richness of Islam, and Islam in its perverted form had attempted to destroy it. But the original power of the culture itself, and the people, like Haidara, who had become entranced by that power, had saved the great manuscripts in the end.

Timbuktu had witnessed the killings of scholars by the Emperor Sunni Ali in the 1300s, the rise of the anti-Semitic preacher Muhammed Al Maghili in the 1490s, the edicts of King Askia Mohammed banning and imprisoning Jews during that same decade, and the implementation of Shariah law in Timbuktu by the jihadis in the early and mid-1800s. The city seemed to be in a constant state of flux, periods of openness and liberalism followed by waves of intolerance and repression.

One of the works that spoke most to me is volume called Waffayat Al Ayan Libnu Halakan — a kind of medieval Encyclopaedia Britannica, originally written in the mid-thirteenth century by a Kurdish scholar named Ibn Khallikan, chronicling the lives of the ulema, the great Islamic scholars, of the tenth through twelfth centuries. The capsule biographies were arranged alphabetically, written in blocks of squiggling Arabic script in black ink, broken periodically by illuminated single lines of red, blue, and gold. Each time the scribe commenced a new section, he changed the color of the ink.

Scores of scholars over the centuries had added commentaries to the original work written by Ibn Khallikan, who had studied in Damascus and lived most of his life in Cairo, filling the margins of every page with notes written in tiny Arabic characters.

In many places the original paper had deteriorated, and new bits had been glued carefully into place, giving the manuscript a worn patchwork appearance, like a beloved article of clothing that had been mended over and over again. They show the number of times it was restored, degraded, and restored. The great intellectuals give a work like this a lot of importance. Each notation is dated, and marked by name of the author, in the manner of Talmudic commentaries, scholars noting one another’s arguments, debating fine points of law and ethics, their dialogue continuing down through the centuries. One commentator would take a phrase from the work, and give his opinion about a point of jurisprudence.

The encyclopedia functioned as a kind of pre-Internet chat room, with the conversations attenuated over hundreds of years. Such encyclopedias proliferated during Timbuktu’s Golden Age, reflecting a desire to give coherence and order to Islamic scholarship from Timbuktu to Egypt and beyond, to confer recognition, even immortality upon learned men who had sought to enlarge the scope of human understanding. They were a Who’s Who of the medieval Islamic world, and they represented an extraordinary achievement at a time when that world was a far bigger, far less interconnected place, and collating the biographies of scattered scholars required exhaustive time and effort. The vigor and durability of Timbuktu’s intellectual life seemed tangible here, in both the original text and the ancient commentaries of savants through the ages.

700,000 books survived in Timbuktu. They run from documents from the medieval Sudanese empire of Makuria, written in at least eight different languages, to key texts of Islam, including Korans, collections of hadiths (actions or sayings of the prophet), Sufi texts and devotional texts, works of the Maliki school of Islamic law, texts representative of the ‘Islamic sciences’, including grammar, mathematics, and astronomy, and original works from the region, including contracts, commentaries, historical chronicles, poetry, and marginal notes and jottings, which have proved to be a surprisingly fertile source of historical data.

And this is what I loved about Timbuktu. It is beyond a place — it is a stream of dreams and hopes, with open-minded people adding their thoughts to a living record of our journey. We are all a part of the Timbuktu story — or stories — because we have had passed to us the gentle wisdom of our fellows.

Each of them, through the centuries, felt the same fears as we do, and had the same pains and pleasures, yet took the time to reward us — who of course they could only imagine, never meet — with the best heritage they could assemble.

Timbuktu is the haven where gold became less valuable than knowledge, and we are grateful for it.

I knew only the tip of this story when I was there. I had worked at the Arrive & Wait restaurant to earn my air fare to Accra in Ghana, and had hitch-hiked from there to Timbuktu. Many adventures swirled by along the road, and they shall be treasured. I was evicted from the city regarding that incident with the bare-breasted women, but I hold no grudges. I had taken photos of the boats in the Niger, and there were women washing clothes there. They were uncovered from the waist up; I had given it no thought until the police arrested me for illegal activities. As I was leaving the country, though, I happened to be in a shop at the border crossing and saw a postcard. It featured women, uncovered, washing clothes in the Niger. I bought the card, addressed it to the police chief, added my own thoughts, stuffed it into the mailbox, and hastily jumped on the next truck out of Mali.

In comparison to the other great scribes of Timbuktu, my contribution was perhaps shallow.

But sincere.

In any event, it’s a great place, and I heartily recommend it…after the violence dies down.

Written by Barry Gander

A Canadian from Connecticut: 2 strikes against me! I'm a top writer, looking for the Meaning under the headlines. Follow me on Mastodon @Barry

What a great story! I only wish the Timbuktu library did beat Al Qaeda. One can still get killed for looking at the wrong book or admiring a woman’s anatomy in many places in MENA even today. The closing of hearts and minds seems to be accelerating and I am mystified for a solution. 😢

Fascinating account. When I was young I wanted to see all of the interesting places of the world. Timbuktu sounded very exotic then. Travel has changed though. It used to be adventure and discovery, now it’s a business and a hassle. (Or probably I’m just too old & tired?)

Thanks Barry for some good old armchair traveling.